The Momentum of Gesture in Art und Religion (7)

Ernst Jandl’s poem Zweierlei Handzeichen from his collection “Laut und Luise” (Sound and Luise) very simply expresses the difference between religiously and artistically motivated hand movements:

I cross myself

in front of every church

I plumicate myself

before every orchard

Jandl goes on to remark laconically that every Catholic knows the gesture of crossing himself – he alone knows the gesture of bezwetschkigung (plumication).

It would now be possible to speculate about the meaning of the hand gesture of the Bezwetschkigung (Plumication). One could also ask why a poet combines two sign gestures in such a way and in turn presents this combination in a poem in a very gestural way. However, this would probably have the usual consequences: The very esprit that is at work in a poem when it condenses words into language art for a moment evaporates when it is taken apart into its individual parts.

Every successful poem is a momentum. The flow of words pauses, from which the words of a poem emerge. Much of what was spoken before and after then turns out to be empty talk. This is another reason why a failed poem hurts towards the closing of the eyes or the ears.

Every successful poem knows that it holds an eloquent moment ready for us. The best poems wink at us from the edge of silence, as if they will evaporate in the next moment. “Just now an angel floated through the room” is said about a moment of eloquent silence in which the gear of speech stops. When those breathlessly chasing their thoughts with words pause, the spirit can breathe a sigh of relief.

Could an angel floating through space, if it existed, do this of its own accord? Or would it need something to move it? The breeze that moved an angel is that of esprit when it withdraws from the chatter of communication into the momentum of a poem. That is why a poem, when it gives asylum to the wit of language, is also called “witty” (geistreich).

The experience of the literary unsealing of a poem through its interpretation is probably familiar to all students. It is similar to the experience of theological interpretation of biblical texts. It is instructive how a text can lose its wit through interpretation and exegesis. What then seems as mindless as the interpretation itself, which has dissected it, prepared it and padded it with meanings, is a dried-up angel with glass eyes. Poems that have fallen among scholars therefore often merely perch with withered feathers on an amature of wired concepts.

Given the intergenerational practices of exorcising the spirit (Geist) from art, it borders on miraculous that and how poems retain their presence of spirit (Geist), like metaphors, despite the permanent attempt to grasp them to death, remain alive.

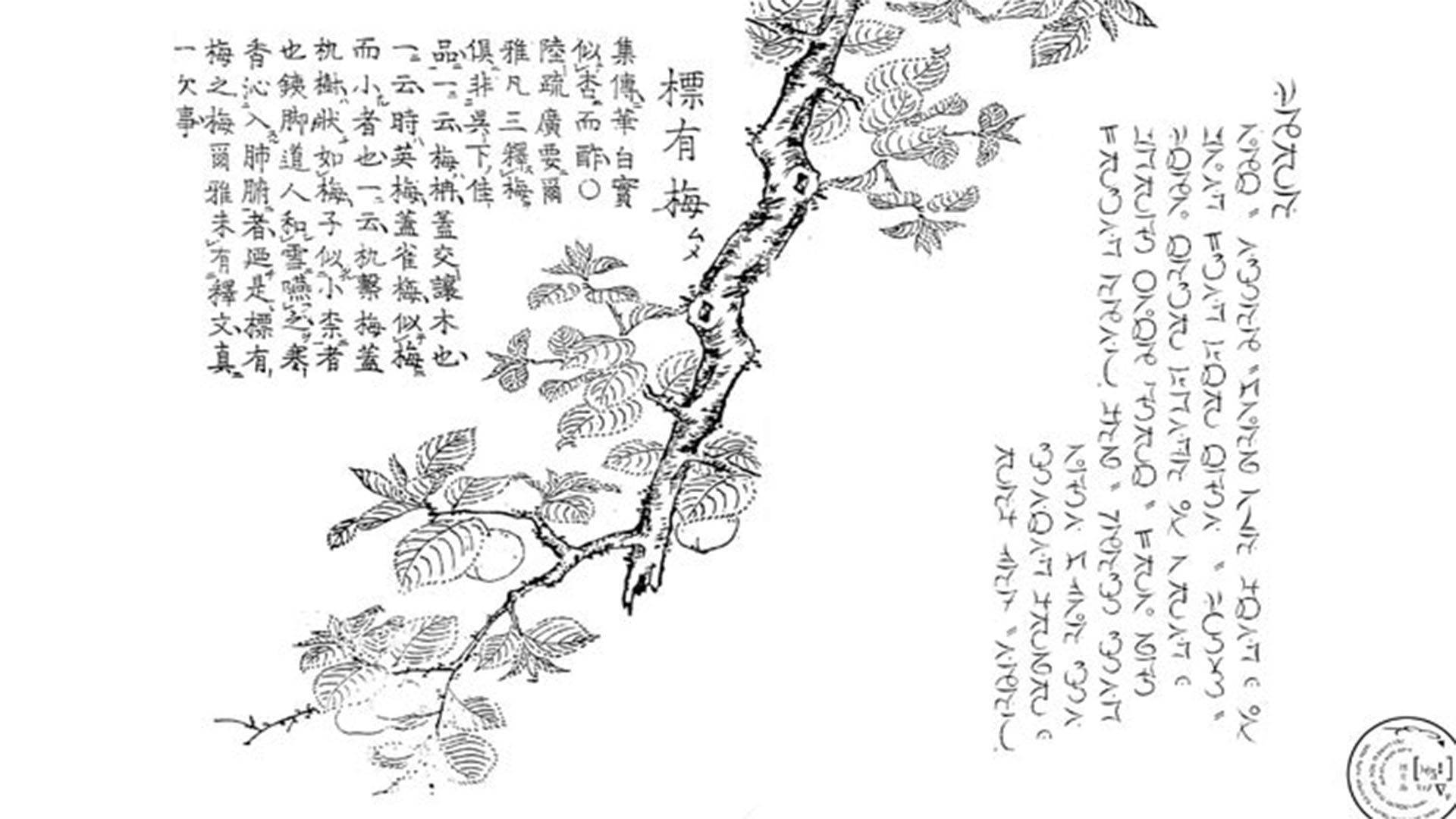

That is why we can follow one of the hints that the esprit in Ernst Jandl’s poem gives us. Orchard wood that could bear fruit. The sign gesture of confinement could perhaps communicate, if we understood it like the believers of crucifixion, what we can expect when the time is ripe.

But to know what fruit living wood might bear, sometimes it is enough to look at the leaves. In his poem Der Pflaumenbaum (The Plum Tree), Bertolt Brecht pointed out very beautifully how even a small tree can survive the attempt to drive out its urge to develop by imprisoning it.

Even seemingly dead and bent wood that has been made into an instrument can still show what it is made of. For example, a walking stick planted in the right place. From a theological point of view, such a thing is a miracle and as such God’s work – which is why this image is often used in sermons. In 1849, Carl von Killinger described in his Sagen und Mährchen how the king’s walking stick helped Saint Kiran to get a building site for a church. It is true that the king did not actually want to give away the most beautiful sheep pasture in Ireland for this purpose. But the sprouting stick was a sign from God enough. A sign from God, a simple sign that immediately indicates that the Spirit of God is manifesting itself here and now. As a gesture of nature that testifies that even something dead can be breathed back into life.

Sometimes, when praying, believers wish to experience a moment of touch in which God communicates Himself to them. They do not expect much. Just a small gesture to show them that they are noticed, even seen. Sometimes believers try to transfer the lyrical form of the poem into the liturgical form of prayer. For example, by praying a psalm: “Do a sign (אֹ֗ות, σημεῖον) to me (give me a hint) that I am well …” (Psalm 86:17). עֲשֵֽׂה-עִמִּ֥י אֹ֗ות לְטֹ֫ובָ֥ה וְיִרְא֣וּ שֹׂנְאַ֣י וְיֵבֹ֑שׁוּ כִּֽי-אַתָּ֥ה יְ֝הוָ֗ה עֲזַרְתַּ֥נִי וְנִחַמְתָּֽנִי׃

Not everyone, however, is blessed with apparitions and signs, like Teresa of Avila. At Pentecost 1563, the mystic was granted pneumaphanies that touched her deeply and conveyed God’s message to her: “I want you from now on to deal no longer with men, but with angels”. (Autobiography v 24,7). One of the “signs from which the beginners, the advanced and the perfect can see whether the Holy Spirit is with them” is the appearance of the dove: “During this contemplation I saw a dove above my head, but it was quite different from the local doves, because its wings had brightly shining little shells instead of feathers. It was also larger than the usual pigeons, and I seemed to hear the rustling of its wings. She hovered over me for about a Hail Mary.” (V 38, 9-10).

Even art practitioners sometimes resort to the form of prayer to introduce us to the spirit that in a dream makes an unexpected wish fulfilment grow out of a word, as Rose Ausländer does in her poem Hunger:

Behind the Back

of the automatically watchful angel

dream high

the tree

So what is it that connects a clue sign trace (Hinweiszeichenspur, אֹ֗ות, σημεῖον) of the working (wirkenden) spirit with the gestures in which it shows itself?

Robert Krokowski