The Momentum of Gesture in Art and Religion (13)

The artistic, especially performative working through of religious gestures is always exposed to the risk of intentional or unintentional misunderstanding – and the risk of self-misunderstanding. For sometimes a close examination of a work of art or a self-description of artistic activity reveals that there is a difference between intended and observed performance.

So when Ulrike Lynn attempts with poems of a sacred nature to place words as linguistic gestures in a liturgical context, it raises the question of whether the tightrope walk between religion and art, between lyrical confession and confessing poetry can succeed. Are the linguistic gestures of her poems that seek physical contact with the divine, in the context of an auditory sacred “setting”, part of the mystery of the liturgy? Or do they manifest a personal drama in the attempt to transform words that stick to the palate like hosts into poems that are meant to taste of solutions?

In her gesture performances, Marlen Wagner works with pointing and wise gestures. Her gestural dexterity questions the manner of giving instructions just as much as the finger-pointing-at-something-or-someone gesture. The gesture and habitus of those who assiduously behave as those who point the way and act as those who judge is made visible and legible through shifts in context.

Libertad Esmeralda Iocco brings the gestures of angels into movement in her dance performances. In her workshop, she develops gestural movement forms and dances together with the participants. What becomes of the gestures of the angels in the process – and what encounters become possible when the conditions are made to dance that are praised by the officials of heaven?

Perhaps sharing in such experiences will shed a different light on the rococo angels of ecclesiastical art, in which believers find a finger pointing to God, while the sculptor himself may have had in mind here the depiction of a far less sacred rendezvous. A closer look at Ignaz Günther’s “Guardian Angels”, which finds here the still of a rococo dance, also makes this group of figures a conundrum. It may be that the angel is pointing towards heaven. But his whole demeanour points to a different concern for people than the faithful want to see. A trace that leads to the question of what the Nephilim are all about.

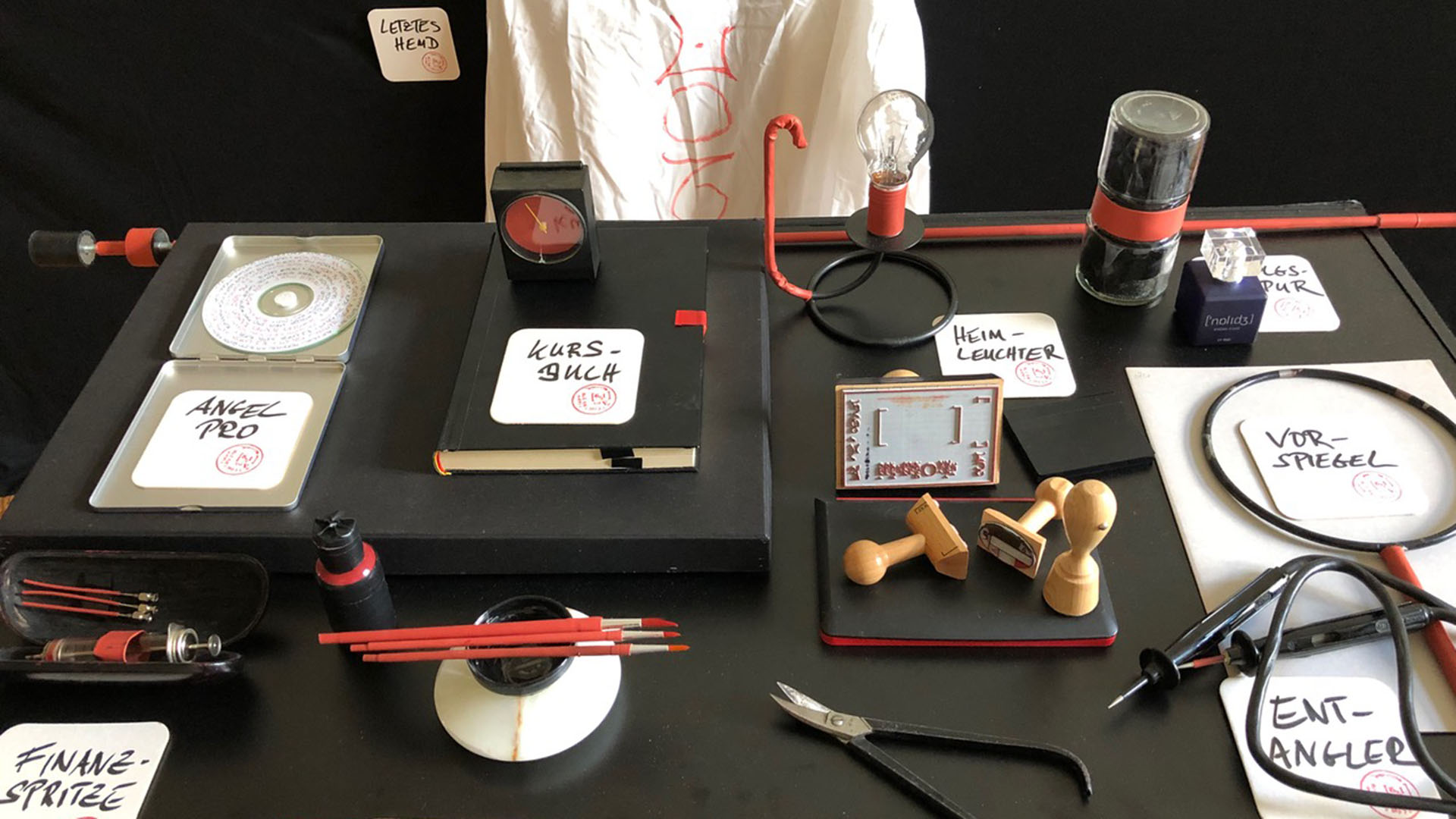

And if I myself am on the trail of the gesture that invites people to participate in the aesthetic process in art (in dance, in performances, in gestural, pictorial, written and sonic assemblages and in poetic texts), then I too ask myself why the heavenly fowl appears in so many different ways in dreams: As Bruno Ganz, as Nephilim, as red characters, as Lucifer-Amor, as an angel dancing with Jacob at the Jabbok, as Klee’s Angelus Novus or as Barbara, whose performance gave me an interpretation of what message the pinboard of my collection of moments was conveying. Or as a business angel who confronts those who dream of success with the functions of a home chandelier, the dangers of a financial injection, a censored course book, an empty forehead, a tensionless entangler and at least the last shirt before issuing them a certificate of success.

Art practitioners who engage in the faith business of the churches expose themselves to the pull of religion – especially when they are praised to the skies or imagine themselves in spheres from which the abyss of the world yawns at them. Who can permanently resist the temptations of faith when the danger of falling seems to loom at every moment? In fact, however, the evocation of the danger of falling from heaven or falling into the abyss of hell is one of the scenarios of those who do not want to and must not under any circumstances allow the thought of escaping. I wonder what the angels will do when they cease to be ministers or assistants in the state of God administered by the churches – and when art has granted them asylum and their activities no longer consist of administrative acts and praise of the existing order. And what will become of those who practise the arts if they allow themselves to be civil servants of churches and the liturgical gesture is transformed into personal habitus? And what becomes of artistic practice itself when the “incredible need to believe” (Julia Kristeva) is no longer sublimated into art – but is transformed into religious faith? Would poetic mediation between the cultures of art project spaces and church congregations still be possible then – or would poetry and practice become a mystical profession of faith, would poetry itself become a text form of mystery, dance a cultic-ritual event, performance part of liturgical faith management?

Gestures can therefore be mediators between cultures, they can translate the dialogue between art and religion into aesthetic practice. Art practitioners share a passion with believers: that suffering may not have the last word. It is one of the “bets” of art to which art practitioners invite and have always invited believers: How is joy possible on the path of acknowledging, working through and sublimating suffering – without instrumentalising faith for all-encompassing forbearance and without institutionalising a compassion that threatens to infantilise the suffering individual and turn him or her into an object of concern? How, then, in the words of Paul, is the experience of kairos possible, in sensing the parousia of the weak messianic power?

“Suffering, like joy, cannot communicate itself immediately and completely: This is basically what post-Tridentine art says; it can only express itself through transposition, displacement, ellipsis or condensation, in the flesh of words, sounds, images. To the point of laughing at one’s own suffering, to the point of desacralising suffering through the gesture of representation that acknowledges and tames it.” (Julias Kristeva, This Incredible Need to Believe, 2014, p. 94)

Robert Krokowski