The Momentum of Gesture in Art and Religion (6)

Transfiguration is Raphael’s last painting. He worked on it until his death in 1520. The Vatican museums say that it represents “something like a spiritual legacy of the artist”. The altarpiece “depicts” two episodes of the Gospels. It tells of the “transfiguration” of Jesus and the healing of an epileptic boy. In fact, the painting shows a momentum that condenses two events in time and space into one representation. This momentum is an instruction to the viewer of the painting in ways of the spirit to show itself gesturally. The configurations of gestures, their composition and their interaction in the painting, demonstrate the transfigurations of the spirit, its transformation into manifestations.

The laying on of hands and the stretching out of hands have a high significance in religions. It is questionable to understand them solely as gestures that accompany speech or as gestures that lend emphasis to the logos, the word. Just as the magic wand is not merely the agent of the spell to enchant someone, a gesture is not merely the execution of God’s imperatives, the carrying out of his instructions. The gesture embodies the spirit, without which the word would remain powerless. It would remain inaudible without the breath that carries it and gives it its breath. The spirit does not need the word to blow. But without the word, the spirit remains speechless.

Gesture, as the connection of spirit and word, instructs those who consider both to be their own. Through gesture they are reminded that usufruct of property is different from use of a spiritual property – or, of course, abuse of spiritual power. To need the Spirit and the Word is different from appropriating both and, in contemporary terms, accumulating, capitalising and instrumentalising, exploiting or abusing, consuming or exterminating. Gestures are indicative of a needing of the spirit that is not absorbed in the sign-use of those who believe they have it at their disposal.

There is a long tradition of considering spirit (πνεῦμα, spiritus, רוח) as the cause of illness. Something is messed up, something is missing, something is too much, something is in places where it does not belong. Healing – understood as restitutio in integrum – is meant to restore a disturbed wholeness and order. Even today in German it is said that people “are left by good spirits” if they do not behave as expected. The history of the treatment of epilepsy shows how unusual, “abnormal” behaviour disturbs people. They look for a cause for it, or better still, causers. Believing in possession by an evil spirit is an easy explanation. It makes the sufferer the possession of an evil-causing spirit that uses him for its purposes.

Pneuma (πνεῦμα), that is, spirit that produces foam (ἀφρίζων), is out of place and must depart. This is the basically simple message of the apostle Mark (9:12-29). But how can spirit be caused to give way? Why do the followers of Jesus find it so difficult to heal a possessed person? Why are they as powerless against such possession as a small group of Jews confronted by the legions of the Roman occupiers? Obviously, it is not always easy to find the right faith when usage, ownership and possession are in dispute. Especially as the obsessed often accuse others of false obsession; the enthusiastic accuse others of misguided enthusiasm; the enthusiastic suspect others of enthusiasm for the wrong cause; fanatics often denounce others as dangerous fanatics. So who possesses the right spirit – and who is possessed by the wrong one? How, then, is the true, the right, the correct faith to be recognised?

Mark’s Gospel gives a surprising answer to this: faith can be recognised by the fact that it is successful. So he who believes successfully is right. This, too, is a religious heritage that until recently was still inherited by science and medicine: He who heals successfully is right. The shoulder-shrugging phrase “faith moves mountains” was a common explanation for successes for which there was no scientific explanation.

The description of the healing of the young epileptic in the Gospel of Mark begins precisely with this: The scholars fail with their attempts at healing. The means at their disposal fail. Their faith fails. And so Jesus has to point out to them that their use of the Spirit testifies to a different custom than that which is required.

The Bible text shows how Jesus reacts to the inability to use faith correctly with rather gruff words: How often shall I actually tell you …: ὦ γενεὰ ἄπιστος, ἕως πότε πρὸς ὑμᾶς ἔσομαι ; ἕως πότε ἀνέξομαι ὑμῶν – O faithless generation, how long am I to be with you? How long am I to bear with you? (Mark 9:19) For, Jesus said, it is really quite simple: πάντα δυνατὰ τῷ πιστεύοντι – All things are possible for one who believes. (Mark 9:23). Is this not an incredible statement? Especially for its addressees, who see themselves as believers.

First, then, the situation: there is a boy possessed by an unclean (ακαθαρτω) spirit, which drags him to and fro, sometimes throwing him into the fire and sometimes into the water, making him deaf and dumb (πνεῦμα ἄλαλον, κωφὸν, Mark 9:17 and 25). The only means of letting him out (ἐξελθεῖν), Jesus said, was to pray (τοῦτο τὸ γένος ἐν οὐδενὶ δύναται ἐξελθεῖν εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ) (Mark 9:28).

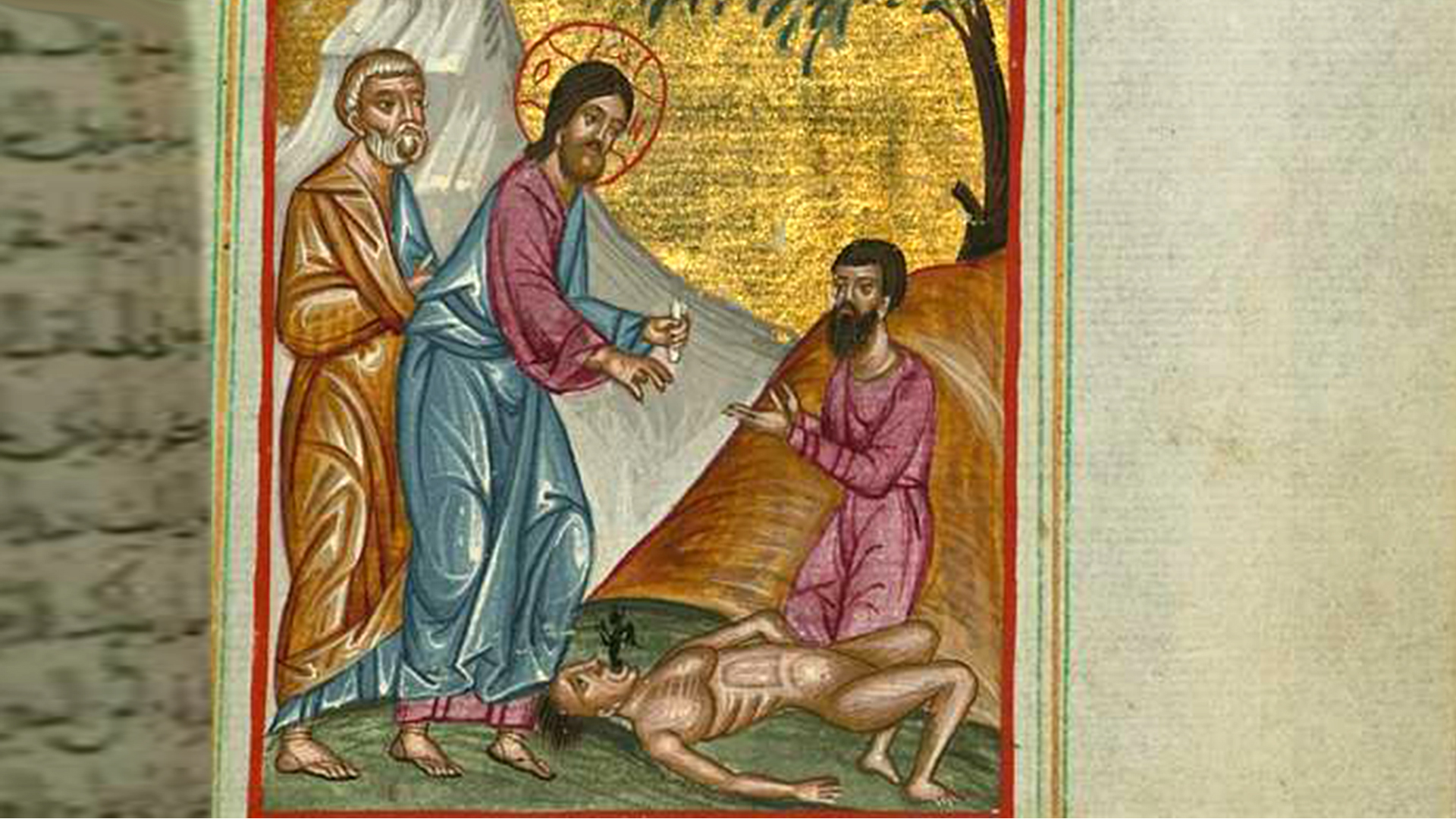

Raphael’s altarpiece depicts the prehistory of the redemption of the possessed man from his suffering, as the momentum of the Spirit in transfiguration. It turns out that spirit can be embodied by different agents: here not only by the resurrected Jesus (as soma pneumatikon) but also by the spirit-possessed people (as soma psychikon). (From Paul’s perspective, one could say: Raphael’s painting depicts a messianic time in which the Second Coming (παρουσία) of the Christos, the Anointed One, the Messiah is imminent).

Looking at the boy’s hoped-for deliverance from his suffering (Mark 9:12-29), from a possession that Matthew (17:15) also calls “moonstruck” (σεληνιάζεται, lunaticus), Raphael sets an impressive condensation of a gesture play of spirit healing. The gestures demonstrate the working of the spirit, or more precisely: the spirit demonstrates in the gestures its power, its possibilities and its mutability. It is this “sign” (semeion) that believers and prayers hope for when they ask not for a specific sign, but for a hint, a characteristic, a trace that a spiritual connection has been established in prayer.

In his General Audience on 12 November 2008, Benedict XVI spoke about the expectation of the Parousia, the coming of the Risen Christ, as Messiah, in Paul’s view. He calls it a “given of Paul’s teaching on eschatology” that “Jews and Gentiles” are united in the “universality of the call to faith” and that this is a “sign and anticipation of the future reality” in which the after becomes a before.

(Those who understand “sign” more in the tradition of scientific theories of signs will find Benedict XVI’s use of the word in this context disconcerting. The Greek word that appears in Paul’s letters, but also in the Gospels and in the Acts of the Apostles, when referring to the presence of the Spirit, is semeion (σημεῖον). Gestures, then, testify to the efficacy of the Spirit. In this respect they only signify something to someone when they are understood as signs. But the Apostles in their Gospels, as also Paul in his Epistles, as even Benedict XVI in the passage quoted, refrain from pointing out what is being pointed to. They do not convey a concept of what is happening. They bring up its spirit. Whenever semeion appears as a signifier, there is no pointing out of what is being signified. When semeion is spoken of, one cannot actually “imagine” what is meant when it is said “There is a semeion.” This is similar with a bodily gestural indication. It witnesses the movement of the communication as such, the transmission of a “to be communicated”, not the designation of a communicated).

The gestures in Raphael’s Transfiguration are sage gestures. They show, depending on the movement choreographed by Raphael, both the possession by spirit of those acting in the painting and spirit as their possession, as well as its abuse. It is this that proves the gestures to be sages, gestures of pointing to something, of rejecting, of instructing, of referring, of instructing or rejecting, the attitude of those authorised to instruct, of the sages called to instruct and those not called to instruct. (There is a merely untranslatable play with the word “weisen” in German. It ist opposed zu “zeigen” passim in the text.)

Robert Krokowski