The Momentum of Gesture in Art and Religion (2)

What literally sets believers in motion, physically and spiritually, in their religious activity? What motivates them to pray? What causes them to move in a certain way when praying? And why then are some stirrings and excitations pleasing to the one as whose agents the angels appear – and others not? So what happens when people pray?

It is often not easy with the rules, messages, gestures and agents of faith. The fact that it is not proper for children to fidget on church pews when praying does not quite fit in with the fact that the actions of the dervishes are apparently quite pleasing to God. And the trance jerks in vodoo will only be considered inappropriate by Catholics if they think the enthusiastic raptures of mystics are epileptic seizures. What are Jews doing at Kotel, the Wailing Wall? And why do Kathakali dancers roll their eyes so much? Why do some fold their hands, others place them together with their palms, others let them rest on their knees and some stretch them up to the sky?

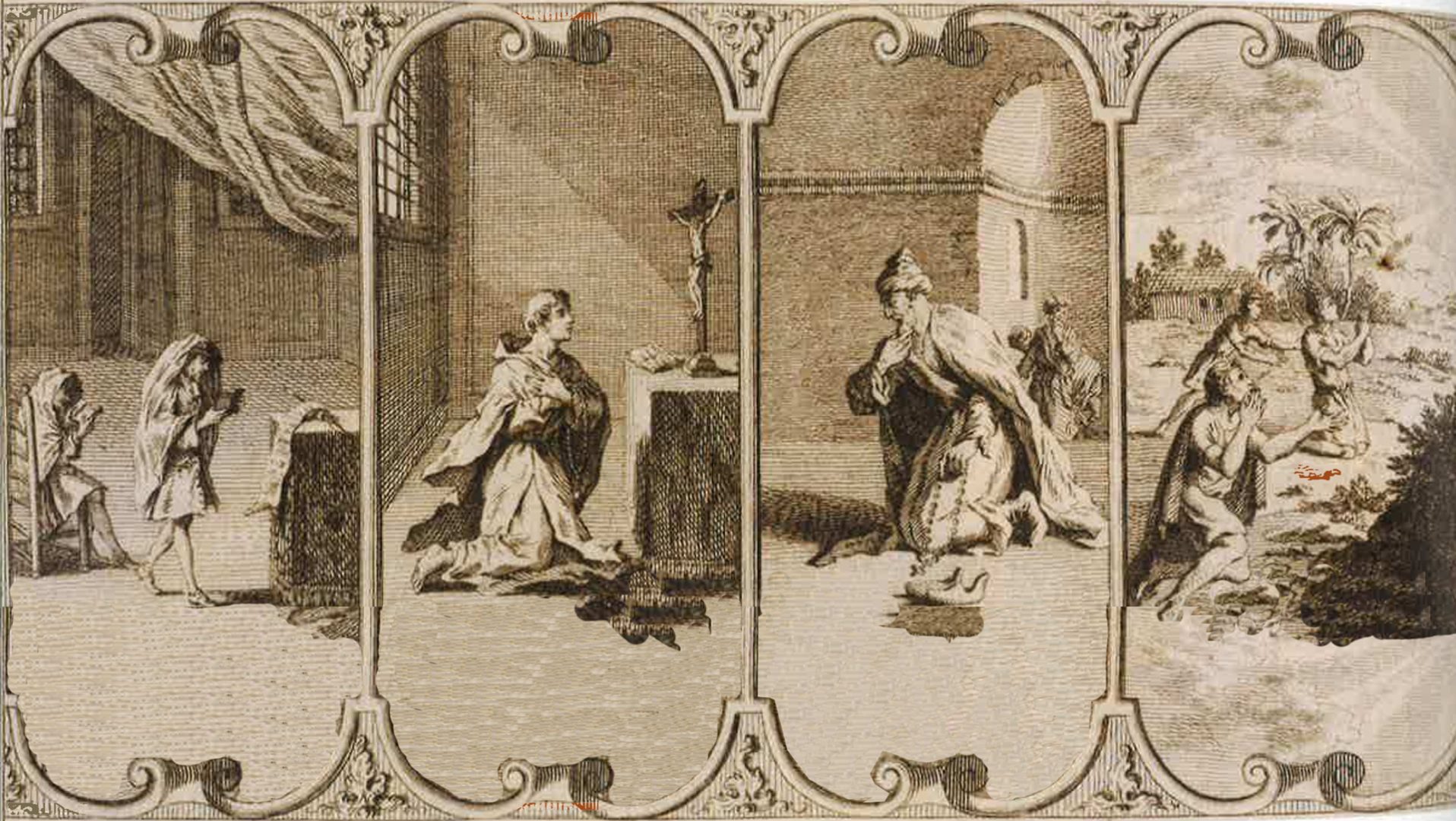

Gestures and physical movements are part of the rituals and cults in all religions in which believers want to get in touch with God. His invocation can have many reasons. Sometimes it is to receive a sign or a word. Sometimes the arms are spread out to receive the spirit of God.

What does gesture research say about prayer gestures? Can science capture the process of gesture formation in religious dialogue situations with conceptual distinctions? From their point of view, are they rather speech-accompanying gestures or emblematic gestures? And on the other hand, what contribution can gestural research make to understanding motivation and intention, drive and purpose, direction and goal, purpose and meaning, conscious and unconscious parts of movements and gestures? What do believers do when they move while praying?

Christians associate the gesture of bending the knee or kneeling (genuflexio) and the genuflection (venia) with the gesture of crucifixion – or not. When prostrating (prostratio and metanie), the whole body can form a cross if the arms are stretched out horizontally from the body. Some Jews shock (rock) violently at the Sh’mone esre prayer – others do not. Muslims bow (ruku’) three times in prayer at Subhana rabbija-l-‘adsim, praising the Exalted One, with their hands on their knees and perform sadshda (prostration) three times while the tips of their toes and knees touch the ground. And in voodoo, the souls of the hounsi (children) are understood to be angels (grand-bon-ange, big good angel, and petit-bon-ange, little good angel) who must leave the bodies. Only then can those dancing around the central pillar serve as containers for the Iwa (spirits). And only then can they respond to questions with messages.

The movements of the bodies in prayer thus seem to connect all religions, just as the movements of the bodies in art connect the cultures. Gestures, which are formed from hand movements and finally understood as signs, are part of the event. However, the meaningfulness of gestures seems to be more important to the doctrine of faith as well as to science than the enthusiasm they are evoked by. What inspires gestures, what spirit sets them in motion, how enthusiasm makes them dance is sometimes not a good sign for administrators of the “right” faith.

Robert Krokowski