To see is to believe

In the Middle Ages, seeing meant believing, is Uwe Fiedler’s conclusion of the video in which he describes the Holy Sepulchre, which has been given into the care of the Chemnitz Schloßberg Museum, as a theatre of figurines of the biblical Easter story.

The Holy Sepulchre from Chemnitz’ Jakobikirche, created between 1480 and 1520, is back in the Schloßbergmuseum since October 2001 after extensive restoration work. The late Gothic staging made of lime wood is modelled on a Gothic cathedral without sanctuary. The Passion of Christ (Passion and Easter story) is depicted on two levels of the transportable magnificent shrine. The pedestal serves to hold the body of Jesus taken down from the cross.

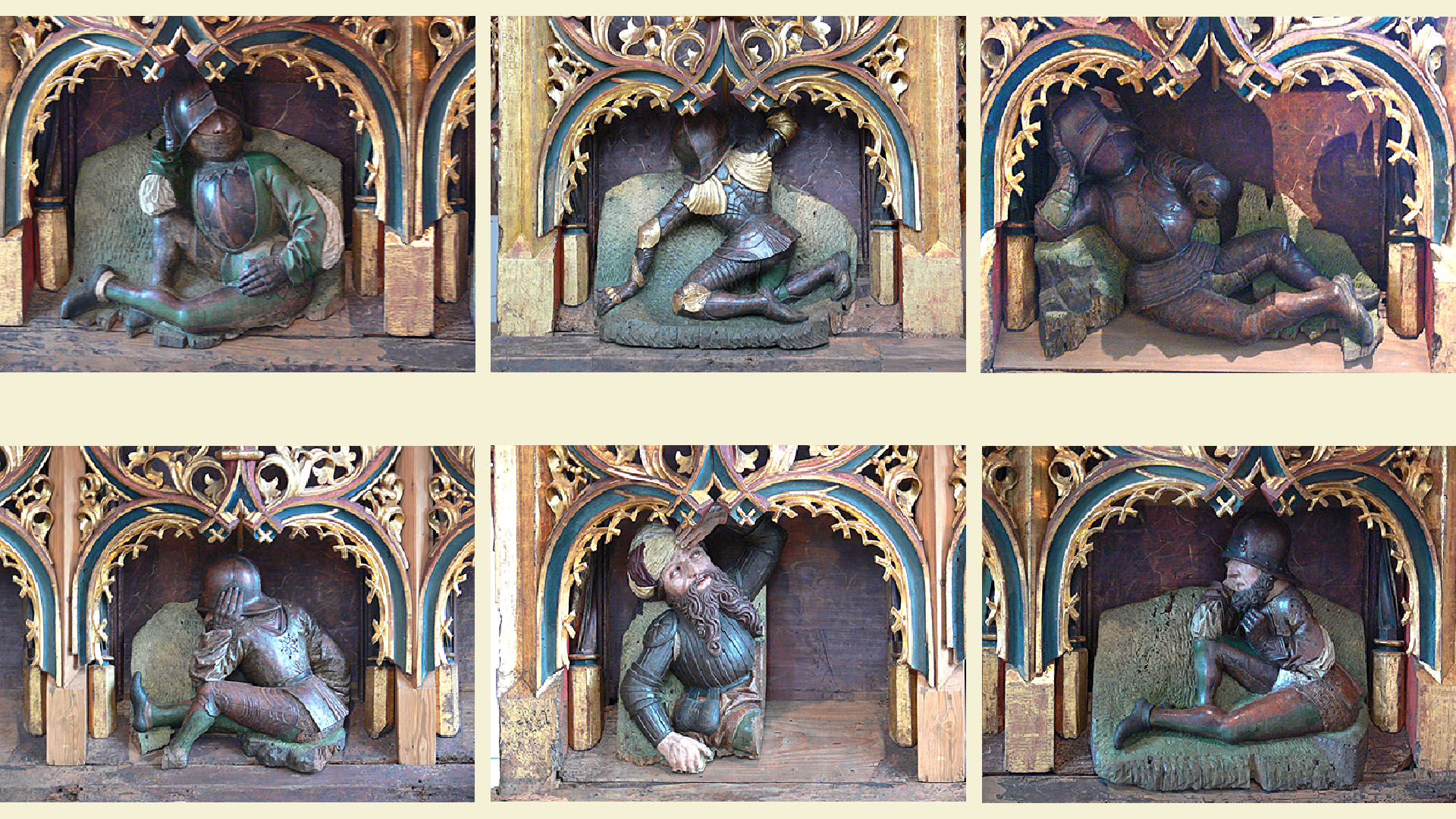

Crouching and lying on the pedestal level are the guards commissioned by Pontius Pilate to prevent the ancient biblical prophecy from being fulfilled, according to which one resurrect from the dead and rises from the grave.

For you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption. You make known to me the path of life; your presence there is fullness of joy; your right hand are pleasures forevermore. (Psalm 16:10-11)

The guards seem drowsy, all shielding their eyes with the visors of their helmets and/or turning away from the action. But one of the guards raises his head, turns his eyes upwards and shields them with his right hand – against what? It can only be a shining light into which he gazes as he awakens, for the New Testament does not report any witnesses to the resurrection except in the apocryphal Gospel of Peter. The Gospel of Matthew, however, reports of an angel whose

(…) appearance was like lightning, and his clothing white as snow. And for fear of him the guards trembled and became like dead men. (Matthew 28:3-4)

The appearance of the angel causes the guards to freeze.

On the second level of the splendour shrine freestanding sculptures are placed on consoles.

On the “Good Friday side” is Joseph of Arimathea, who asks Pontius Pilate’s permission to bury the body of Jesus. The mother Mary and probably Mary Klopa (also Mary Cleophas/Kleophae) are also found here, mourning as if they were still standing by the cross:

but standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. (John 19:25)

Placed on the narrow side that belongs to the Good Friday side, is Nicodemus presents the instruments of Christ’s torture, the crown of thorns and the three nails with a gesture of his two hands stretched forward and open. Nicodemus’ left hand and the tools are missing today. In his video (Link) the director of the Schlossberg Museum, Uwe Fiedler, conveys this gesture very vividly.

Mary Magdalene (Mary from Magdala) stands on the Easter side, radiant with joy at Jesus’ resurrection, as do Jesus’ disciples, Peter and John Evangelista.

On the second narrow side, a wingless angel stands on his console. Over his left arm he has draped the shroud of Jesus, his right hand lies over it as if protecting it. This is the angel of the resurrection standing on the “Easter side” of the holy tomb. He carries the empty shroud and thus signifies: The tomb is empty – Jesus is risen.

The “Angel of the Lord” only appears in the flesh at this one point in Matthew’s Gospel, otherwise angels proclaim their messages in dreams. Matthew dresses him in a white robe:

(…) and his clothing white as snow. (Mat 28:3) and thus clearly identifies him as a heavenly figure belonging to God, sent by God who acts through them.

The Chemnitz angel of the resurrection wears a golden robe, following on from Luke 24:4, which describes his heavenly messengers in dazzling apparel. No one witnesses the resurrection, for only the angel rolls away the stone before the opening of the tomb. He therefore appears after Jesus’ resurrection and shows the women the empty tomb, which Jesus has already left. John also attributes to the risen Jesus the quality of being able to pass through closed doors, through walls:

Eight days later, his disciples were inside again, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you.” (Jn 20:26)

The angel is the guarantor of the resurrection and therefore shows the empty shroud as confirmation. To see is to believe.

It is not without reason that the robe of the angel of the resurrection is white (or shining, golden), as this establishes a backward analogy between him and Jesus.

During Jesus’ transformation in Mt 17:1-9, his face and clothing change:

And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became white as light.

Mt 28 describes the shining face and white robe of the angel of the resurrection in the same sequence in which Jesus’ transfiguration takes place.

Passages that speak of Jesus’ coming resurrection immediately follow:

And as they were coming down the mountain, Jesus commanded them, “Tell no one the vision, until the Son of Man is raised from the dead.” (Mat 17:9).

The Transfiguration transforms Jesus, the Son of Man, into the Son of God through His very Father:

He was still speaking when, behold, a bright cloud overshadowed them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.” (Mt 17:5).

It anticipates his later resurrection and already hints at his astral body that can walk through walls. The similiarity of the angel of the resurrection to the transformed Jesus is thus intentional, the angel a retrospective reference to Jesus before his resurrection. Now, after the tomb is empty and Jesus has risen, the angel sits down on the stone that has been rolled away by his own hand, as if to emphasise: Behold, here I sit as a guarantor that the transfigured one is now the resurrected one. To see is to believe.

There are many angels of the resurrection in art. They open the tomb, flank the risen Jesus with hands folded in prayer, or triumphantly stretch up one arm with an outstretched hand and index finger pointing upwards – while the other arm usually points downwards at an angle to the open tomb. The Chemnitz angel of the resurrection does not show such a dramatic gesture, nor one of loud praise or silent prayer. He stands calmly on his pedestal, smiling reservedly at those looking at him. While Nicodemus presents the instruments of torture with a speaking gesture on the Good Friday side, the angel holds the cloth. It lies quietly over his arm, no breeze moves its drapery. Like the angel, it simply is. That is quite enough to authenticate the resurrection.

When Chemnitz’s Jakobikirche became Protestant after the Reformation, the holy tomb narrowly escaped destruction. It was only preserved out of “pedagogical” insight, of which a plaque that no longer exists proclaimed in 1668:

We do not honour it, but we tolerate it and place it in this worthy place, because it preaches the holy doctrines to the unlearned people.

For two days during the Middle Ages, the Holy Sepulchre stands in the church at Easter and tells the Easter story to believers. On Easter Sunday, the shrine is cleared away and churchgoers see a new scene: the risen Christ holding the flag of the cross/victory and clothed in the red mantle of the ruler. Further visualisations are offered by the Catholic Church to instruct its faithful: On Palm Sunday (10 April), a wooden figure of Christ rides through the streets on a donkey, commemorating Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. On Assumption Day (15 August), as late as the 1960s, a figure of Mary Mother of God on a throne is carried through the streets in the Ruhr area on a sedan, accompanied mainly by women and children singing and praying as they scatter flowers along the way. At Christmas, the nativity with Joseph and Mary, the Christ child, ox and donkey illustrates the biblical events.

Marlen Wagner