In the three great monotheistic religions – Christianity, Judaism and Islam – angels play an essential role as messengers, as mediators between God and man. The mere fact that they appear in the three religions connects them with each other. If we look more closely at their appearances, we can see that there are certain angels who appear in more than one religion.

Rafael counts seven archangels in the Book of Tobit 12,15: “I am Rafael, one of the seven holy angels, who carry up the prayer of the saints and with it come before the majesty of the holy God”. There are seven angelic princes in Christianity until Pope Zacharias and the Synod of Rome in 745 reduce their number by four and only allow the worship of the biblically attested Rafael, Michael and Gabriel.

Uriel (אוּרִיאֵל “the light of God”/”my light is God”), in fact, is the source of the dispute between the churches regarding the Roman Catholic and Eastern Church liturgies. In the canonical writings Uriel is not listed, but in the rabbinical and gnostic writings and the apocrypha. In addition to Uriel, depending on the sources, Inias, Adin, Saboak, Simiel, Raguel, Barachael and Pantasaron lay claim to the four princely titles that have been rejected in Christianity until today. The host of archangels in Judaism includes, in addition to Uriel, Rafael and Gabriel, Chamuel, Haniel, Jophiel, Raguel, Sariel, Ramiel and Zadkiel.

The Quran names only four malaʾika (angels): Israfil, who announces the Day of Judgment by blowing a trumpet); the angel of death, Azrael; Mika’il, who is responsible for natural events; and Jibrīl (Gabriel), who serves as the transmitter of revelation to the Prophet Mohamed. Reverence is not paid to them, however, unlike in Christianity. For completely subordinate to Allah, dependent on his will, they can do nothing without his instruction, nothing against his will.

The name Gabriel is common in Hebrew ( גַּבְרִיאֵל) and means “God is my power”, but also “man/help/power of God”. He delivers God’s messages in all three religions: In Sura 2, 97 it is Gabriel who sends the Qur’an as good news into the heart of the believer. Luke 1:26-31 tells of the angel Gabriel announcing to Mary the good news of her conception of Jesus. And in Daniel 9:21-23, he delivers a word from God to Daniel so that he can draw clear insight from the vision.

All three religions also know a rebellion of the angels after God created man.

Genesis 1 verse 26 says: “Let us make a man in our image and likeness; and let him rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air”. Psalm 8 is put into the mouths of the angels as an answer to this: “what is man that you remember him, and the child of man that you take care of him? 6 You have made him little lower than God; with honor and glory you have crowned him. 7 Thou hast made him lord of thy hands’ work; all things thou hast put under his feet (…).”

The angels obviously understand here that with the creation of Adam the previous relationship between God and angels will change. Man, from their point of view, is endowed with a stronger power than they themselves. Man and his descendants are placed higher than the angels. Therefore, they rebel and will not bow the knee to Adam as God commands them.

In a Jewish narrative, as reported by Islamic scholar Nicolai Sinai of Oxford Pembroke College, God puts the angels in their place by asking them to give names to every creature and thing. At this task the angels fail, since they cannot know more, than which God had told them. The human being, Adam, however, solves this task without problems, since he is equipped after the image of God, thus with the power to create. Satan does not appear in Jewish monotheism as an adversary of God, but as an accuser in the divine court against man.

Although without own will, also in Islam the angels rebel. They, too, protest against the appointment of man as Allah’s governor (khalîfa) on earth. Man, created from clay, from dirt, is imperfect, wicked, they say. He is a being with the possibility to choose. To choose between good and evil, right and wrong – not bound by the will of God. Inherent in him is the possibility to rebel.

Before him, those created from pure light do not want to kneel down. Allah also succeeds in ending the rebellion of the angels. All angels but one submit to his will and bow down before Adam. This one bears the name Iblîs. He wants to do the right thing, his allegiance is exclusively to Allah. Therefore, he understands his refusal to kneel before Adam not as disobedience to Allah, but as an affirmation of his loyalty to him. Allah, however, rejects him because of his arrogance and counts him among the unbelievers from now on (Sura 2, 34).

But Allah teaches the newly created Adam the names of all things, of all living beings – and thus elevates him above the angels, who “have no knowledge except what you (Allah) have imparted to us (before)” (Sura 2, 32). The rejected Iblîs becomes شيطان “Shaitan” (Satan). In Islamic popular belief, he lives on as a malevolent demon, an enemy of man.

Whether the rebellion of Lucifer and his fall are ultimately also based on the competition between angels and humans regarding God’s favor is not entirely clarified in the Christian interpretation. A need to rise again, born of inferiority and the consequent belittlement, may have moved Lucifer to compete with God himself, even to outdo him: “I will ascend into heaven and exalt my throne above the stars of God (…)”, he declares in Isa 14, 13. But from the heights of heaven he falls, the “beautiful(r) morning star (…) down into the realm of the dead (…) (into) the deepest pit”, Isa 14, 15. As an angel fallen from the heights of heaven, he becomes the prince of the depths, of hell – and as God’s eternal adversary, he is still in a certain sense his equal (if one follows the Mephistophelean stories) as his adversary, since in Goethe’s tragedy, for example, he describes himself as “A part of that power, / Which always wills evil and always creates good.” (V. 1335-1336).

This literary take on the motif of the fallen angel has not gone unchallenged. Jürgen Drewermann, for example, thinks that – for instance, if one thinks of the declared intention of Iblîs – one can recognize that, on the contrary, the will to always do good leads to evil …

In general, the history of interpretation shows that the light that is thrown on the angels is often a result of interpretive sovereignty. They are not epiphanies in themselves, but for someone, an observer. And since this observer is always a human being, the question arises as to his desirability of observing angels as straightforwardly docile or transversely rebellious.

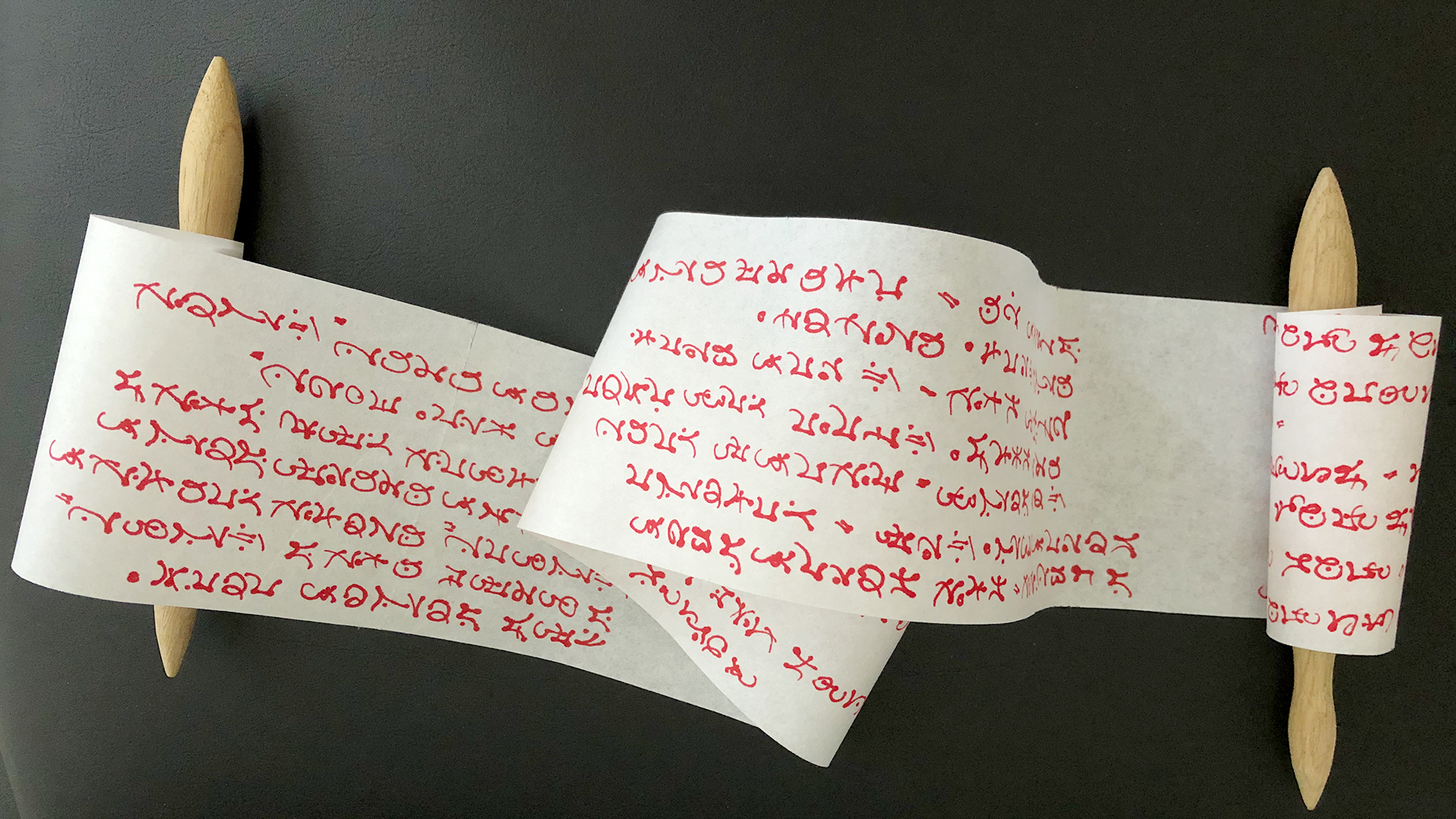

The Book of Enoch vividly shows with which linguistic means a “scribe of justice” puts his perceptions of “fallen angels” in the service of dogmatic interests.

Marlen Wagner