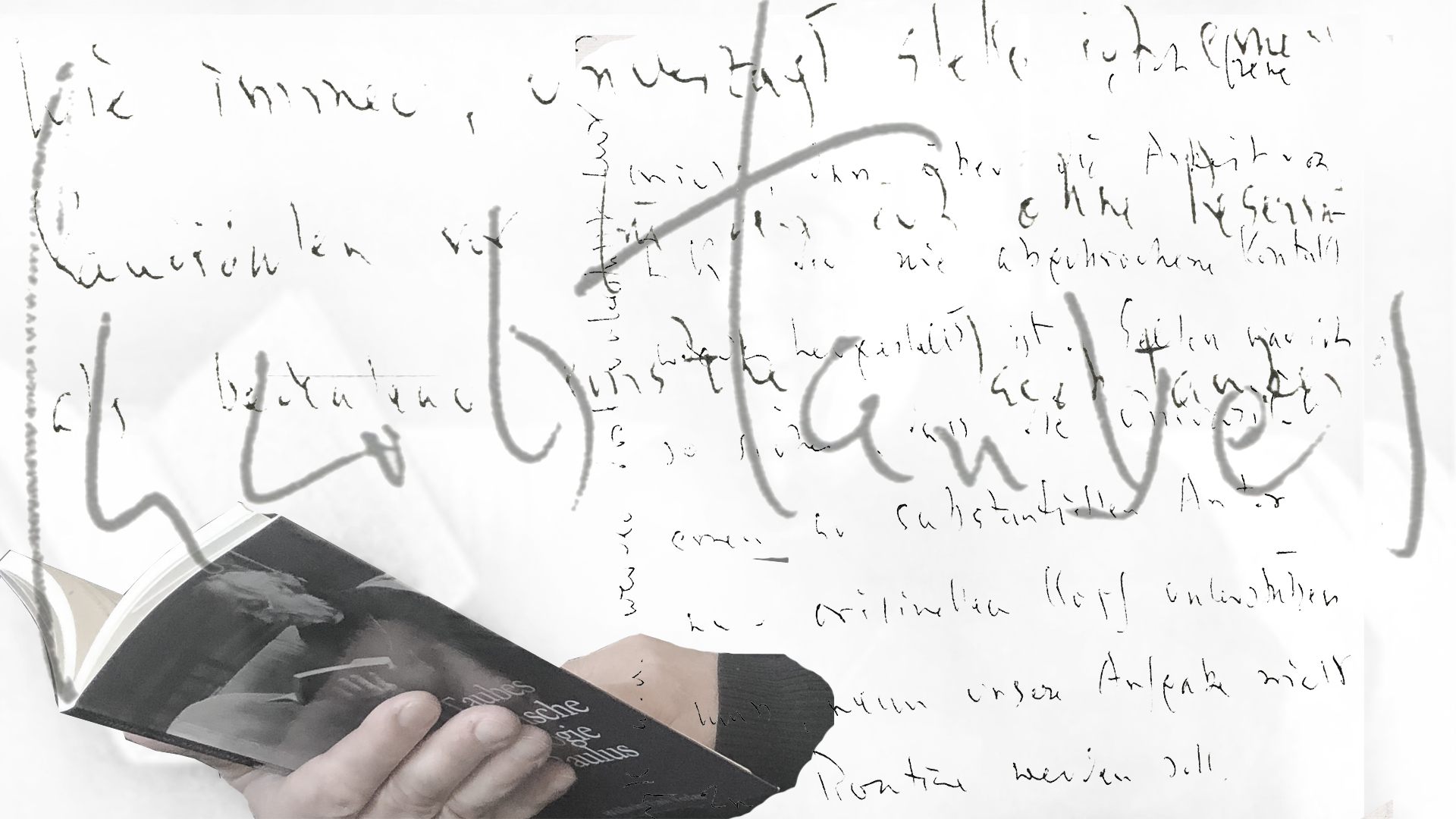

The Momentum of Gesture in Art und Religion (10)

There are gestures that make us feel welcome for a moment. Among these are those generous gestures that remain unforgettable because they invite us in a special, intentionless way to make common cause while at the same time encouraging us to do our own thing. Perhaps the most beautiful thing about a generous gesture is that it expresses its invitation to acceptance in a very restrained and cautious way, and only gently touches the hands that accept it, not chains them.

When Susanne and I came to Berlin in the early 1980s to continue and expand our studies, we suspected what an exciting time lay ahead of us – but not what we were then actually allowed to experience: We attended the lectures and seminars of Jacob Taubes and Klaus Heinrich unabashedly in parallel. We did acrobatic mental somersaults between Walter Benjamin’s Trauerspielbuch and the discussions about ruin in baroque and posthistoire at Hannes Böhringer’s kitchen table. We argued about the Zeitgeist on display in the Gropius-Bau and enjoyed the intellectual freedom of all the scope Berlin offered at the time.

Allan Kaprow gave a Happening lecture at the UdK, Norbert Haas translated Lacan’s writings in his seminars, Heidi Paris took Polaroids of every visitor at Merve and I stuck my tongue out. Together with Christian Kupke we published the magazine Delta Tau, with writing games inspired by Arno Schmidt and James Joyce. Klaus Laermann polemicised against our cheeky and disrespectful subversivities by drawing us in the Kursbuch of dance rage and Derridadaism. In Hilmar Werner’s salon we discussed the abysses of Genet’s texts with Ina Hartwig, Stephanie Castendyk became our first publisher, Wolfgang Ernst roamed the tableaus of Verschichte with us. In the evening, Einstürzende Neubauten and Peter Stein’s productions or with Heinz-Werner Lawo in the video bar Korrekt in Moabit for drinks on self-designed beer mats and art historical studies on document research. Gerti Fietzek told us about hidden personal traits in Lawrence Weiner’s Concept Art and with Horst Denkler we analysed Zettel’s Traum, even though he rather liked to follow in the footsteps of Wilhelm Raabe. Klaus Leymann raved about Lucia Popp’s voice in our library and with Thomas Flemming we followed Adorno’s traces in Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus.

There were often gestures in these encounters that I remember well. Each one would be worth its own story. The way Klaus Vogelgesang gave up trying to cut a steak with a blunt knife in our kitchen on Beusselstraße is unforgettable. Or the hand gesture with which Michael Theunissen handed me back my first volume of essays, “Schwellenkundliche Versuche”, unread, after he had looked through the table of contents. Or the wave of the hand with which Peter Gente pointed me to the place on the Merve shelf where Adorno’s lecture notes were, saying, “But the cat was in there.”

There were many friendly and amicable gestures, which in memory make one cheerful and grateful: When Norbert Rath smilingly filled the almost always tight apartment-sharing fund in Beusselstraße during his visits and left books there. When Richard Faber invited me to dinner after we had discussed his collage essay. And when Klaus Regel continued to take guitar lessons from me, even though I thought I couldn’t really show him anything anymore. Because there wasn’t much time to practise. A scholarship ran out, money was tight and the dissertation had to be finished.

I had studied theology and philosophy with Jürgen Ebach, Günter Brakelmann, Willi Oelmüller and Norbert Rath at the end of the 1970s. We read the Torah and Hittite cuneiform texts in parallel. We discussed myths of the origin of the world in Philo of Byblos and the auratic in Benjamin’s philosophy of art, the connections between the dialectic of the Enlightenment and scientific-theoretical approaches of positivism, first, second and third nature, Christian social ethics and Adorno’s Minima Moralia. But I was particularly drawn to the writings of Walter Benjamin – and to his explorations of history and the messianic age. Jürgen Ebach was very supportive and encouraged me when I told him about my plans to continue my studies in Berlin. In 1980, I enrolled at the Free University for Philosophy, Religious Studies and Jewish Studies, got caught up in the mills of university restructuring of the doctoral regulations and sought solutions to the precarious situation.

I took part in Jacob Taube’s seminar on Benjamin’s theses on the concept of history. I went to his office hour to give him my Schwellenkundliche Versuche as well, in which there was a long chapter on Benjamin’s threshold experiences. A short time later, as I walked past the Parisbar on Kantstraße in Charlottenburg, Taubes waved at me through the window. I didn’t feel meant and went on my way.

A few days later the phone rang. I heard Susanne talking to the caller for quite a while. Then, when she handed me the receiver, Jacob Taubes answered. “I’m having some visitors from Paris on Sunday and we’re going to talk. I’d like you to be there. Can you come in the afternoon?” Of course I could, very anxious to see what circle awaited me.

So on Sunday afternoon I drove into Grunewald as far as Koenigsallee and strolled across the bridge at Hasensprung towards the Terrassenbau, where Jacob Taubes had his flat. He introduced me to his visitors with a round arm gesture and suddenly made reference to our magazine project: “You’ve been slated in DIE ZEIT – that impresses me.” We laughed. Then he talked about my studies – why had I chosen that topic? And I bubbled away and talked about Benjamin’s early writings and the correspondence with Gretel Adorno, about Klee’s Angelus Novus, the references to Jewish mysticism, the theological-political fragment and its relationship to the theses on the concept of history, the sentences of the rosary and about the relationship of dialectical images to the concept of allegory in the Trauerspielsbuch, of allegorical living to the literarisation of living conditions. I spoke about Jewish messianism and that it particularly interested me.

Jacob Taubes interrupted me as he slid forward on the edge of his chair and leaned towards me: I will probably never forget the gesture he then made. And between his slightly raised hands he then calmly but firmly put the words, “But there is not only Jewish messianism, there is also the Messiah.” I stumbled for a moment. He looked at me. And I said, “Yes, of course …”

Then he asked me about the state of my work. I told him that against the turmoil of institutional reforms, I had already gained a supervisor for my dissertation in Frank Benseler in Paderborn. And then Jacob Taubes said with an inviting gesture: “Why don’t you write your thesis with me? Bring me your synopsis by next week and you’ll have started work before the new doctoral regulations.” I was speechless for a moment – something that rarely happened to me at that time. He smiled. “So it’s a deal.” Then he turned to his other guests and dove into the details of a publication project with them. I don’t remember what it was about. But I remember Jacob Taubes’ three generous gestures that afternoon clearly.

More were to follow. He supported me with an expert opinion for a scholarship. He handed me copies of personal letters to addressees whom he probably thought could sponsor me. Jacob Taubes died only a few months later. I did not succeed in finding another supervisor for my dissertation. But I didn’t really try either. Events in Berlin at that time condensed too quickly. I was too attracted to psychoanalysis and semanalysis, associated with names like Jacques Lacan and Julia Kristeva.

In the academic field of the universities at the end of the 1980s, there was as little time and place for these as there was for ZeiTRaumkünste, as I already called them back then, on the threshold between art and non-art. It was to take another 15 years before it became possible to put all these experiences of the 1980s on course not only artistically and textually, psychoanalytically and semanalytically, but also in university teaching.

And it was to be another 15 years before I took up my studies of the 1980s again. In contemporaneity of the demise of the Catholic Church and the simultaneous rise of religious fundamentalism, in times of the transformation of science into religion and the global perpetuation of the political state of exception, Jacob Taubes’ generous gesture of placing the question of the Messiah between his hands led me once again on the trail that Giorgio Agamben had followed so persistently in the meantime. What is the time that remains – and what need calls for action that takes into account what the religions understand as the messianic spirit? Who or what is the katechon today, the one who or that stops, the one who or that lives from crisis management? And what gesture could invite us to experience the time that remains together in such a way that hope springs from faith in love?

Robert Krokowski